Toshiko Takaezu

1922–2011

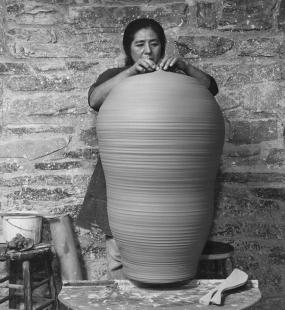

Toshiko Takaezu, 1974; Photographer Evon Streetman, Toshiko Takaezu papers, circa 1925-circa 2010, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt or make pots that cannot be used. An artist is a poet in his or her own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive.

Arguably the preeminent ceramicist of the past century, Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011) is renowned for her experimental glazing techniques, which capture the movement of action painting through her expert application of multiple glazes. While critics have often discussed her work in relation to Japan and Eastern approaches to art-making, Takaezu’s practice of applying pigment and glaze by pouring, dripping, brushing, or even finger-painting owes as much to action painting and abstract expressionism. Her process of acting upon the clay combined with her mastery of throwing and firing techniques has yielded a corpus of visually complex works with enormous tactile appeal.

Takaezu was one of eleven children born to Japanese immigrant parents in Pepeekeo, Hawaii, a small rural community on the east side of the “Big Island.” Her parents were from Okinawa and raised their children in a traditional Japanese home, with her father working as a farmer and laborer; the middle child, Takaezu referred to herself as the “navel child” of her family, as she had five older and five younger siblings. In 1940, she dropped out of high school to work at the Hawaii Potter’s Guild, a commercial ceramic studio in Honolulu, where she acquired a foundational knowledge of ceramic processes, materials and techniques. Takaezu’s formal ceramic education began in 1944, when she began taking pottery lessons led by an officer in the US Army Special Services division who was stationed in Hawaii to perform topographical research; the officer encouraged Takaezu to pursue her creative interests while taking her to openings, plays, and concerts that exposed her to other artistic disciplines.

In 1945, Takaezu left the Potter’s Guild to work at a ceramic production facility located in a woodworking mill, where learned molded production ware and glaze chemistry techniques. There she met the ceramicist and sculptor Claude Horan, who became a highly influential mentor to the young artist. Feeling the need for a greater creative outlet, Takaezu began taking painting and drawing classes at the Honolulu Art School in 1947, where Precisionist painter Ralston Crawford was one of her instructors. The following year, she enrolled at the University of Hawaii to study under Horan, who had recently taken a faculty position there. Studying at UH from 1947–1951, Takaezu also took design and weaving classes while developing her ceramic practice, exhibiting her pottery for the first time at the prestigious Ceramic Nationals exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, NY, in 1949. It was in these years that the artist developed her earliest examples of closed-form ceramics, which grew out of Horan’s approach to similar bottle forms.

In 1951, Takaezu relocated to Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, to attend the Cranbrook Academy of Art. “Hawai’i was where I learned technique,” she later recalled. “Cranbrook was where I found myself.”[1] At Cranbrook, Takaezu studied under Maija Grotell, a Finnish-American ceramicist whose work had inspired her interest in the school. Acclaimed for an artistic philosophy which advanced the idea that ceramics could be a fine art akin to sculpture, Grotell emphasized self-discovery and an embrace of individuality in her teachings; Grotell became a formative mentor for Takaezu, not only in the development of her practice, but also in her own approach to teaching - an endeavor Takaezu would pursue later in life. Takaezu brought volcanic sand from Hawai’i to Michigan, which she mixed into some of her clay works. She also minored in textiles, learning weaving techniques from another Finnish teacher, Marianne Strengell, who taught her how to make Nordic ryas, a shaggy hand-knotted wool rug, which Takaezu later incorporated into her practice.[2]

In 1955, Takaezu traveled to Japan for the first time to glean a deeper understanding of the nation’s culture and connect with her heritage. The young artist spent eight months there, studying traditional and contemporary ceramic techniques, the tea ceremony, and Zen Buddhism. She also met leading ceramicists Toyo Kaneshige and Yagi Kazuo, the latter of whom, like Grotell, focused on nonfunctional vessels and sought to elevate ceramics to the realm of sculpture. Takaezu’s experiences in Japan were foundational to her maturation as an artist, as she acquired a deeper understanding of herself as well as a fresh perspective on the intersection of Eastern and Western creative models: “I returned from Japan with renewed vigor and inspiration. I put into practice what I had learned of the artistry of Japanese ceramics with my own perception of the western world. I threw myself into weaving and painting, too, with tireless energy. I discovered in clay a life of its own.”[3]

Back in the United States, Takaezu took a job as an instructor at the Cleveland Institute of Art in Cleveland, OH, where she oversaw the installation of new kilns and developed her philosophy of sculptural, non-functional ceramics. During the 1950s, the abstract expressionist movement reached its apogee, and Takaezu introduced its ethos into her ceramics and weavings, applying spontaneous pours, splashes, and drips of paint and glaze onto plates and searching for ways to translate this spirit into her volumetric vessels. This effort led to the realization of her signature piece: the closed form, in which the vessels opening is minimized to a tiny airhole and its surface acts as a canvas onto which Takaezu applied expressive layers of glaze.

In 1957, Takaezu attended the first Annual Conference of American Craftsmen at Asilomar Conference Grounds in California’s Bay Area, where she spoke on a panel outlining her philosophy: “In our highly mechanized age, it is important that we have handcraft where we can work with our hands and minds. In a sense this is food for the searching soul … The potters, of necessity, must do more of the experimental pieces. By that I mean, experimental in form and surface, which is a combination of sculpture and painting.”[4] At the Asilomar conference, Takaezu was introduced to textile artist Lenore Tawney, who became a lifelong friend and collaborator.

In 1965, Takaezu left Cleveland and relocated to Clinton, New Jersey, setting up a studio in a former mill and teaching at Princeton University and Skidmore College. In 1967, she had her first monographic exhibition in Hawai’i, at Honolulu’s Contemporary Art Center, and in 1969 was featured in the groundbreaking exhibition Objects: USA, which surveyed the contemporary American craft movement and traveled to thirty-three locations in the United States and Europe.

The development of larger kilns throughout the middle decades of the 20th century allowed Takaezu to increase the scale of her work, which sometimes reached over sixty inches, as in her Tree series of the 1970s. Throughout her career, Takaezu sought to integrate the form of her ceramics with the glazes that covered them; the interiors of her ceramics were also a space she considered to be an important, if invisible aspect of the artwork. She considered the enclosed emptiness of her vessels to be a metaphor for the human spirit and often placed clay beads inside to add an element of sound to the artwork.

Takaezu was also an enthusiastic teacher, mentoring numerous students during her tenure at Princeton University from 1967 to 1992, some of whom went on to apprentice at her home studio. She also received numerous awards throughout her career. In 1964, she received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation grant and a Craftsman’s Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1980. She held honorary doctorates from the Moore College of Art and Design (Philadelphia), the University of Hawaii at Honolulu, and Princeton University. Following her death in 2011, The Toshiko Takaezu Foundation was established to preserve her studio, art, and legacy.

In 1990, the Montclair Art Museum (New Jersey) mounted the retrospective Toshiko Takaezu: Four Decades, which traveled for two years. In 1995, the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, Japan mounted Toshiko Takaezu: Retrospective, which traveled throughout Japan and the United States. Notable solo exhibitions of the last twenty years include Toshiko Takaezu: The Art of Clay at eh Japanese American National Museum, UCLA International Institute, Los Angeles, CA (2005); Echoes of the Earth: Ceramics by Toshiko Takaezu, at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA (2007); Toshiko Takaezu: The OOMA Collection at the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi (2016); and Intuition & Reflection: The Ceramics of Toshiko Takaezu, Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, PA (2021–22). In 2022, Takaezu was included in the 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, The Milk of Dreams. In October 2023, Crystal Bridges Museum of Art in Bentonville, AR, will open Toshiko Takaezu / Lenore Tawney, an exhibition of new acquisitions highlighting the two artists long and formative friendship. Also in 2023, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, presented Toshiko Takaezu: Shaping Abstraction, which focused on Takaezu’s alignment with abstract expressionism. In 2024, The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum mounted the major traveling retrospective, Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within, along with a monograph, co-published by Yale University Press, which stands as the most ambitious study of an American ceramic artist to date. Co-curated by Noguchi Museum Senior Curator Dakin Hart, Assistant Curator Kate Wiener, art historian Glenn Adamson, and composer and sound artist Anne Leilehua Lanzilotti, the exhibition included over 300 works from private and public collections and received rave reviews.

Toshiko Takaezu’s ceramics are in numerous museum collections including the Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, PA; Arkansas Arts Center, Little Rock, AK; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Bank of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI; Bloomsburg University, Bloomsburg, PA; Boise Art Museum, Boise, ID; Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI; Butler Institute of American Art; Youngstown, OH; Canton Museum of Art, Canton, OH; Cantor Arts Center of Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI; Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA; The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, HI; Cranbrook Academy of Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH; Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE; Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA; Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY; Flint Institute of Arts, Flint, MI; Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ ; Harn Museum of Art, Hawaii State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, Honolulu, HI; Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, HI; Hunterdon Art Museum, Clinton, NJ; Illinois State University, Normal, IL; Johnson Wax Collection, Racine, WI; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Milwaukee Art Museum Milwaukee, WI; Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN; Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston, MA; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Houston, TX; Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI; Museum of Arts & Design, New York, NY; National Museum, Bangkok, Thailand; National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, Japan; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; The Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ; Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, MS; Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum, Naha City, Okinawa; Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Museum, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; Princeton University Art Museum Princeton, NJ; Racine Art Museum, Racine, WI; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ; Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA; Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, NE; Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY; University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI; University of Michigan Museum, Ann Arbor, MI; Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery, Nashville, TN; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

[1] Toshiko Takaezu, quoted in Conrad Brown, “Toshiko Takaezu.” Craft Horizons, 19, no. 2 (1959), 23.

[2] Glenn Adamson, “Centering Toshiko Takaezu.” Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within. (New York: The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, 2024), 9.

[3] Toshiko Takaezu, quoted in Glenn Adamson, “Centering Toshiko Takaezu.” Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within. (New York: The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, 2024), 14.

[4] Toshiko Takaezu, “The Socio-Economic Outlook in Ceramics,” in Asilomar: First Annual Conference of American Craftsmen (New York: American Craftsmen’s Council, 1957), 19.

Press