Eldzier Cortor

1916–2015

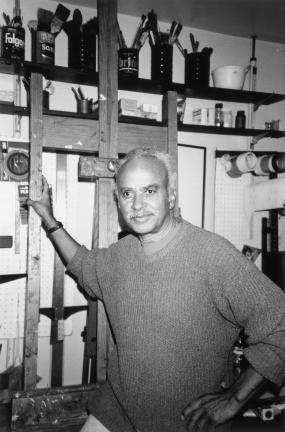

Eldzier Cortor in his studio, c.1995; Photographer unknown

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

The Black woman represents the Black race. She is the Black Spirit; she conveys a feeling of eternity and a continuance of life.

Eldzier Cortor is best known for his surreal paintings of black women in elongated, graceful compositions influenced by the lines and forms of African sculpture. Born in Richmond, Virginia in 1916, Cortor’s father moved the family to Chicago when he was about one year old. Cortor grew up reading the Chicago Defender, a national weekly (at the time) newspaper focusing on and published by Black Americans, which may have influenced his dedication to celebrating Black figures in art. As a teenager, he attended Englewood High School in Chicago’s South Side, where he met Charles Sebree and Charles White.

In 1936, Cortor enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago, where one of his classes involved a formative trip to the Field Museum to see the collection of African sculpture. The dramatic attenuation of the human form and the dynamic postures central to West African art had a tremendous impact on Cortor’s visual sensibilities. He then attended Chicago’s Institute of Design and studied under László Moholy-Nagy where he was exposed to modern theories of abstraction, though he retained a preference for figuration. During the 1930s, Cortor found work with the Federal Art Project of the WPA, and in 1941, with funds from the WPA, co-founded the South Side Community Art Center on South Michigan Avenue. Three years later, Cortor received a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Foundation to travel to the Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia and the Carolinas and study the Gullah community there. As he wrote in his Plan of Work, “I have been particularly concerned with painting Negro racial types not only as such but in connection with particular problems in color, design and composition … Some assimilation of their background and mode of living would add to the authenticity of the paintings.”[1] In the Sea Islands, Cortor found a productive foil to his modernist training: “Abstract art didn’t do anything down there. They did pulp things: the people and things like that, you know, was the material.”[2]

Despite their traumatic history of diaspora and slavery, the Gullah had preserved West African language, food, religion, and traditions in the Americas for generations, often fusing African ways with European ones to create a unique culture. They became a Black American ideal for Cortor, and Gullah women were the inspiration for his visualization of the transcendent spirit of African Americans embodied as a quiet, regal woman.

Cortor began receiving institutional attention with the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual exhibition American Paintings and Sculpture, which included him from 1942 to 1946. At the same time, his work was exhibited regularly in New York at Artists Gallery, Downtown Gallery, and Whyte Gallery, prompting him to relocate to the city’s lower east side.

In 1946, Cortor achieved popular recognition when Life magazine published one of his semi-nude female figures. In 1949, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to travel to the West Indies to paint in Jamaica and Cuba before settling in Haiti for two years, where he taught classes at the Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince. These travels exposed Cortor to more examples of how West African culture survived in diaspora. The symbolic imagery in Cortor’s paintings—birds, gates, shells, windows—resonate with surrealism and also speak to the vitality of African culture—how the old world protected itself from obliteration by hiding in or merging with the imposed culture of the new.

In New York, Cortor encounter printmaking at The Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop, and from 1972 to 1995 he taught printmaking classes at The Pratt Institute.[3] His prints were recently celebrated in the museum retrospective Eldzier Cortor: Master Printmaker at the San Antonio Museum of Art in San Antonio, TX. However, he remains best known for his paintings, which have become exceedingly rare outside of museum collections. They can be found in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; and Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA. His work has also been included in several important museum exhibitions, including Invisible Americans: Black Artists of the ‘30s at The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York (1968), Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston which traveled to The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA (1970), and Two Centuries of Black American Art, organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1976). Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has exhibited Cortor’s work since 1994.

For over sixty years, regardless of trends, Cortor focused his paintings, drawings and prints on “classical composition,” a term he uses to describe the solemn heads and elegant figures of black women. In his later years, his work became more autobiographical, often reflecting past experiences. In his final year, his career as a printmaker was celebrated in the retrospective exhibition Eldzier Cortor: Coming Home at the Art Institute of Chicago (2015).

[1] Quoted in Theresa Jontyle Robinson et al., Three Masters: Eldzier Cortor, Hughie Lee-Smith, Archibald John Motley Jr. (New York, NY: Kenkeleba Gallery, 1988), 13.

[2] Liesl Olson, “Seeing Eldzier Cortor,” Chicago Review, Chicago Modernists, 59/60, no. 4/1 (2016), https://www.chicagoreview.org/seeing-eldzier-cortor/.

[3] Olson.