Charmion von Wiegand

1896–1983

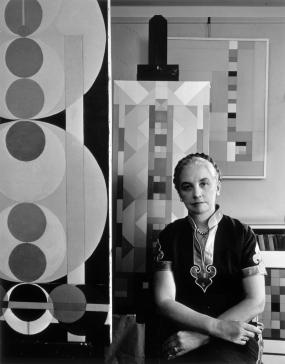

Charmion von Wiegand in her studio, 1961; Photographer Arnold Newman

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

Interior painting starts with the sign. In its initial states it is exorcism—a means of conquering the unknown. It is the oracle, the divination, the symbol of power, evolving from subjective states and moving towards their objective embodiments in a single plastic image.

Known for her abstract geometric paintings that originate a deeply personal language of spiritual enlightenment, Charmion von Wiegand (1896–1983) was born in Chicago but spent her childhood in San Francisco, Arizona, and Berlin. The daughter of a journalist for Hearst, von Wiegand eventually settled in New York in 1915 to attend Barnard College and Columbia University, where she took classes at the School of Journalism while nurturing a growing interest in art history, especially traditional Chinese, Persian, and Indian art. In 1919 she married business executive Hermann Habicht and moved to the suburbs of Connecticut, but soon grew dissatisfied with life as a housewife. A formative event in von Wiegand’s creative life occurred in 1927, when she realized that she wanted to be a painter during a session with her psychoanalyst. Though she continued to pursue a career as a journalist, she also began painting in her spare time, focusing on landscapes and scenes of industrial architecture. Although von Wiegand and Habicht divorced in 1928, they remained friends and he supported her nascent art practice by setting up a studio for her on MacDougal Alley in Greenwich Village. In 1929, von Wiegand secured a position in Moscow as a foreign correspondent for Hearst—the only woman at the desk at the time.

In 1932, von Wiegand returned to New York and married the writer Joseph Freeman, who co-founded and edited the leftist journal New Masses. Von Wiegand began writing art criticism for New Masses as well as for other publications, including New Theatre, ARTnews, and Arts Magazine. When the Abstract American Artists (AAA) held their inaugural exhibition in 1937, von Wiegand reviewed it. An early champion of abstract art, von Wiegand became good friends with AAA founder Carl Holty. In 1941, Holty introduced von Wiegand to Piet Mondrian, who would have a profound impact on her life and art. Fascinated by Mondrian’s artistic philosophy, von Wiegand played a key role in the introduction of his work to American audiences, translating many of the Dutch artist’s writings into English and assisting in the composition of his influential article “Toward the True Vision of Reality” (1941). Through her friendship with Mondrian, von Wiegand embarked on an extended study of neoplasticism in her art and re-kindled her interest in Theosophy, a religion established in the late nineteenth century by Russian mystic Helena Blavatsky that combines aspects of Hinduism, Buddhism, occultism, and esotericism. Von Wiegand’s works of the mid-to-late 1940s reveal an ardent embrace of experimentation. Many works explore a variety of biomorphic motifs conceived through an automatist process—an approach she learned from the modernist painter John Graham and surrealist filmmaker Hans Richter—while others reveal Mondrian’s influence through gridded compositions of flat planes of color. Through both her art and her criticism, von Wiegand cultivated a thoroughly avant-garde social circle that reflected her artistic interests; in addition to Graham, Richter, and Holty, she also maintained friendships with such luminaries as Hart Crane, Sonia Delaunay, Jean Helion, Fredrick Kiesler, Joseph Stella, and Mark Tobey.

In 1942, von Wiegand became a member of the AAA, exhibiting regularly with the group and eventually serving as its president from 1951 to 1953. In the late 1940s, sculptor and fellow AAA member Ibram Lassaw gave her copies of The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book of Life, which inspired von Wiegand to immerse herself in a study of Buddhist art. She began incorporating Buddhist motifs such as stupas and mandalas into her paintings, and her spiritual practice steadily intensified throughout the 1950s. In 1953, her husband gifted her a copy of the I Ching, a Taoist guide for divining meaning from randomly derived numbers arranged in a hexagram—a system the artist readily incorporated into her compositional process. Von Wiegand’s study of Theosophy also intensified over these years, bolstered by her increased access to the religion’s primary sources composed by the religion’s founders and their successors at the New York Theosophical Society’s library.

Another important event in von Wiegand’s artistic and spiritual life occurred in 1967, when she met Khyongla Rato Rinpoche, a Gelugpa monk who had recently arrived in New York as a refugee from China’s invasion of Tibet. Rato soon became a close spiritual companion and guide for the artist, mentoring her engagement with Mahayana Buddhism until her death. In the 1970s she traveled to Tibet and India, where she had an audience with the Dalai Lama. Much of her work from these decades incorporates symbols and schematics drawn from Theosophical prismatic color charts, Chinese astrology, and tantric yoga. In 1975, Rato founded the Tibet Center in New York and invited von Wiegand to sit on its Board of Advisors.

In 1978, the artist was the subject of a PBS documentary titled The Circle of Charmion von Wiegand, which was scored by Philip Glass. In 1980, she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and, in 1982, the Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach organized her first museum retrospective. She died the following year in New York, bequeathing her estate to Khyongla Rato and the Tibet Center of New York. In 1993, the Joseloff Gallery at the University of Hartford mounted the retrospective Charmion von Wiegand: In Search of the Spiritual. As art historians and curators continue to expand the history of spiritual abstraction in the 20th century to include such luminaries as Hilma af Klint, Agnes Pelton, and Sonia Delaunay, von Wiegand’s work has gained institutional recognition and an international audience.

In 1998, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery became the sole representative of Charmion von Wiegand. Since then, the gallery has worked closely with the estate to mount five solo exhibitions highlighting each phase of von Wiegand’s groundbreaking oeuvre, four of which were accompanied by fully illustrated catalogues publishing new scholarship by leading art historians and curators: Spirit & Form, Collages 1946–1963 (1998), Spirituality in Abstraction (2000), Improvisations, 1945 (2003), Offering of the Universe (2007), and Secret Doors (2014).

Recent notable exhibitions that have featured von Wiegand’s work are Histórias da dança (Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand, São Paulo, Brazil, 2020); “Non-Brand (非品牌),” curated by Cai Guo-Qiang for Artistic License: Six Takes on the Guggenheim Collection (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, 2019); Constructive Spirit: Abstract Art in South and North America (Newark Museum, Newark, NJ, 2010); and The Third Mind: American Artists Contemplate Asia (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, 2009).

In the spring of 2023, the Kunstmuseum Basel opened Charmion Von Wiegand, the first retrospective of the artist’s work at a European museum. Originally scheduled to open in 2020, the exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue published in collaboration with Prestel in 2021. Charmion von Wiegand: Expanding Modernism includes a trove of primary document reproductions, a selected chronology, and contributions by exhibition curator Maja Wismer, the museum’s Head of Art after 1960; exhibition co-organizer Martin Brauen, an anthropologist specializing in Himalayan culture; art historian Lori Cole, Associate Professor at New York University; Haema Sivanesan, Curator at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria; Nancy J. Troy, Professor in Art at Stanford University; and art historian Felix Vogel, who currently teaches at the University of Basel.

Works by Charmion von Wiegand are in important museum collections including Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Arithmeum, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany; The Baker Museum, Artis—Naples, Naples, FL; Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL; Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, OH; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens, Jacksonville, FL; Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA; Fondazione Marguerite Arp, Locarno, Switzerland; Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York, NY; Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI; The Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ; Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, MA; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA; Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS; Springfield Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, MA; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT.

Gallery Exhibitions

Press

Publications