Benny Andrews

1930–2006

Benny Andrews, 1976; Photographer unknown, Courtesy of the Benny Andrews Estate.

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

I don’t really think that art really does that much in terms of any kind of social change. . . . And I don’t think any serious artist, and I speak of anyone who practices these professions we call art, could actually sustain any kind of creativity over a period of time if they used it as some kind of social instrument. I think it always remains a selfish outlet for the individual. And even though they’ve thought up kinda nice words for people who try to be creative, the truth is, that if you try to be creative, you really have to be a very selfish, ego-centered person who has this ego to believe that if you do an apple it will convey something that the millions of people who paint apples all the time do not.

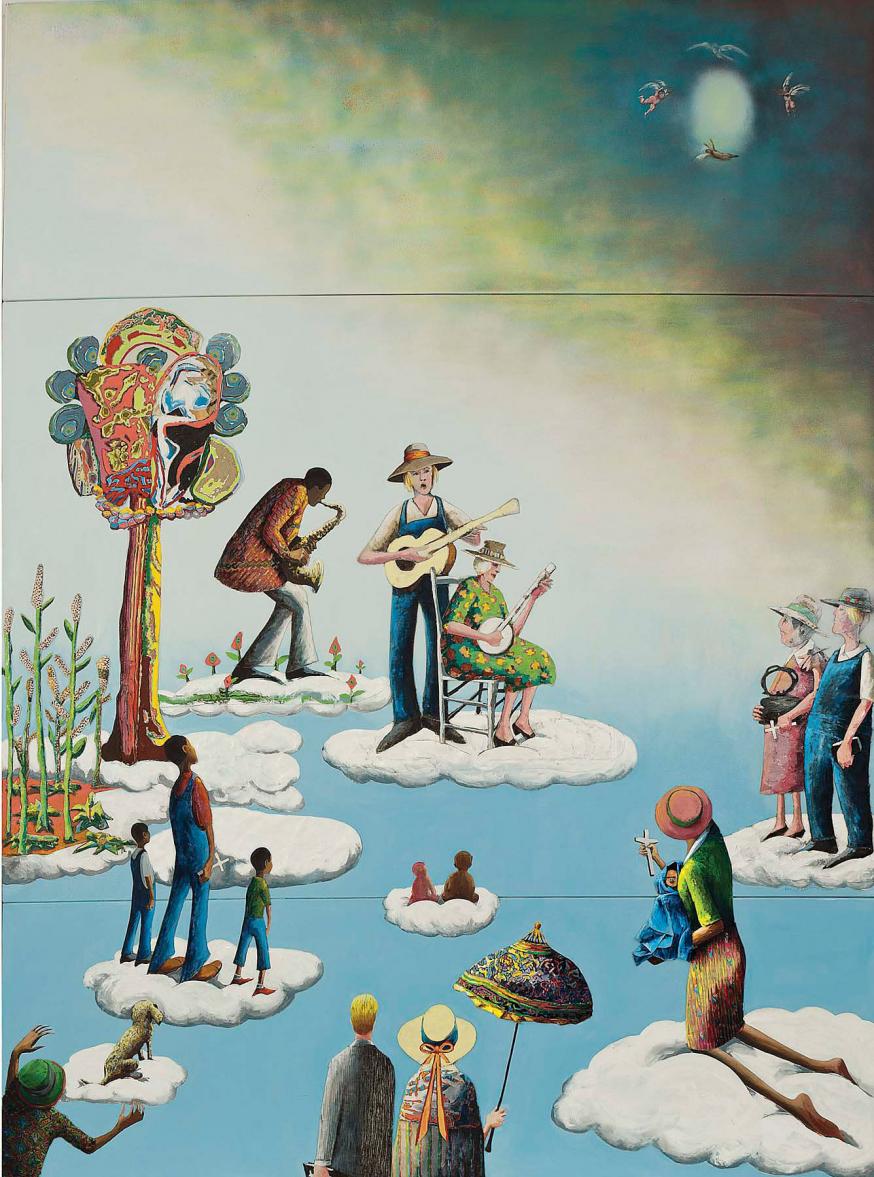

Benny Andrews (1930–2006) is best known for his stirring, vivid collage-paintings that explore themes of race, power, and autobiography through portrayals of Black American life. His signature technique, which he called “rough collage,” incorporated textile fragments into figurative images to produce intricate compositions that meld realism and abstraction. A committed educator and activist, Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), which championed greater representation of Black artists and curators in New York institutions and developed groundbreaking arts education programs for people in prison. As his close friend, Congressman John Lewis, once wrote, “For Benny, there was no line where his activism ended and his art began.”[1]

Andrews was born the youngest of ten children to George and Viola Andrews in Plainview, Georgia, a rural community of sharecroppers near Madison. For the first thirteen years of Benny’s life, his family lived and worked on land owned by the Orr family, which had built its fortune on the labor of slaves before the Civil War. As many historians have pointed out, Andrews’ family history reflects the contradictions regarding race relations in the United States. His paternal great-grandfather, William Jackson Orr, had been an officer in the Confederate Army, and his paternal grandfather, James Orr, spent over fifty years in a relationship with Jessie Andrews, Benny’s grandmother. Andrews’ father, George, worked as a sharecropper on Orr family land. Thus, Andrews was born into a system that closely resembled the system of slavery of his ancestors.

Despite the experience of sharecropping and picking cotton, Andrews recalled his childhood as a happy one. In 1935, Jessie convinced James to build the family a two-room wood-frame house on Orr land close to her own. Andrews began working in the fields as a young child, but he also attended the Plainview Elementary School, a one-and-a-half room log cabin built by the black community in Plainview. Following in the footsteps of his father, a self-taught artist, Andrews began drawing at the age of three; by the time he was in elementary school, he had started to create his own comic characters. In 1943, the Andrews family moved to Madison to work on land managed by C.R. Mason. Because education beyond the seventh grade was severely discouraged, Viola Andrews, determined to provide an education for her children, worked out an arrangement with the Mason family that enabled Benny to attend school when it was not possible to work in the fields. Andrews enrolled in Burney Street High School, graduating in 1948. With a small amount of funding from a 4-H Club scholarship, Andrews enrolled in Georgia’s Fort Valley State College. However, his scholarship ran out after two years, and Andrews struggled with the lack of opportunities to study art. He left Fort Valley and enlisted in the United States Air Force, serving in the Korean War and attaining the rank of staff sergeant before receiving an honorable discharge in 1954. With funding from the GI Bill, Andrews enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1958, he completed his bachelor of fine arts degree and moved to New York City.

In New York, Andrews lived on Suffolk Street, where he met and befriended other Lower East Side figurative expressionists, including Red Grooms, Bob Thompson, Lester Johnson, Claes Oldenburg, and Nam June Paik. He frequented local bars, jazz clubs, and coffee shops, drawing and painting his surroundings. Searching for a visual language to capture the immediacy of everyday life and the quotidian nature of his subject matter, Andrews developed his “rough collage” technique, combining scraps of paper and cloth with oil paint on canvas. As he explained, “I started working with collage because I found oil paint so sophisticated, and I didn’t want to lose my sense of rawness.” By the 1960s, Andrews had mastered this technique, and in 1962, Bella Fishko invited him to become a member of Forum Gallery, which held first New York solo exhibition. Additional solo exhibitions at the gallery followed in 1964 and 1966. In 1965, with funding from a John Hay Whitney Fellowship, Andrews traveled home to Georgia and began working on his Autobiographical Series. In 1966, Andrews was featured in an exhibition with fellow figurative painter Alice Neel at the Countee Cullen Regional Branch of the New York Public Library in Harlem. Both activists concerned with inequality and injustice, they formed a close and lifelong friendship. They also painted portraits of each other: in 1972, Neel completed Benny and Mary Ellen Andrews, which is currently in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, and Andrews painted his Portrait of Alice Neel in 1985.

In 1970, Andrews began working on the Bicentennial Series as a response to the national celebrations planned for the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. Skeptical of the national mood of celebration and nostalgia, Andrews worried about whether the voices of contemporary African Americans would be included as part of the planning. He also feared that black Americans would be omitted from the official forms of national remembrance, or, conversely, that they would be included, but that the considerable contributions of African Americans to US history would be defined exclusively in terms of slavery. In his journal, Andrews described this project as “a Black artist’s expression of how he portrays his dreams, experiences, and hopes along with the despair, anger, and depression to so many other Americans' actions.” The Studio Museum in Harlem presented the first completed works of The Bicentennial Series in 1971. In 1975, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta presented four subseries from The Bicentennial Series; the exhibition traveled to the Herbert F. Johnson Museum, Cornell University, in Ithaca, NY and the National Center of Afro-American Artists in Boston. In 2016-17, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presented Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Series, which included the paintings and drawings for the six individual subseries that make up the whole body of work—Symbols, Trash, Circle, Sexism, War, and Utopia.

A self-described “people’s painter,” Andrews focused on figurative social commentary depicting the struggles, atrocities, and everyday occurrences in the world. His co-founding in 1969 of the Rhino Horn Group (along with Jay Milder, Peter Passuntino, Nicholas Sperakis, Peter Dean, Michael Fauerbach, Bill Barrell, Leonel Gongora, and Ken Bowman) affirmed his commitment to figural work even as various abstract movements gained ascendancy. However, in his mind, art was no substitute for action. To that end, Andrews also embarked on a long career as an educator, activist, and advocate. In 1968, he began teaching at Queens College, City University of New York, where he was part of the college’s SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge) program, designed to help high school students from underserved areas prepare for college. In 1969, he became a founding member of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC), which formed coalitions with other artists’ groups, protested the exclusion of women and men of color from institutional and historical canons, advocated for greater representation of black artists, curators, and intellectuals within major museums, and facilitated art education. In 1971, the art classes Andrews had been teaching at the Manhattan Detention Complex (“the Tombs”) became the cornerstone of a major prison art program initiated under the auspices of the BECC that expanded across the country. In 1976, Andrews became the art coordinator for the Inner City Roundtable of Youths (ICRY)—an organization comprised of gang members in the New York metropolitan area who seek to combat youth violence by strengthening urban communities. That same year, he picketed the Whitney Museum’s John D. Rockefeller III Exhibition of American Artists, which claimed to exhibit 300 years of American art, but contained not a single work by a black artist and only one (white) woman. From 1982 to 1984, he directed the Visual Arts Program, a division of the National Endowment for the Arts (1982-84), initiating a project to enable artists to obtain health insurance. In 2002, the Benny Andrews Foundation was established to help emerging artists gain greater recognition and encourage artists to donate their work to historically black museums. Shortly before his death in 2006, Andrews was working on a project in the Gulf Coast with children displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

Andrews began his final major series in 2004. Titled the Migrant Series, he intended to represent three moments of mass displacement in US history. Between 2004 and 2006, he took three separate trips for this series: following the routes taken by Dust Bowl migrants during the Great Depression, along the path of Cherokee people force-marched from their Mississippi homeland in 1838 on what became known as the Trail of Tears, and to New Orleans and the Gulf coast to study areas devastated by flooding in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. He completed The Trail of Tears in 2005 before dying of cancer the following year.

Several solo exhibitions were organized in the wake of Andrews’ death. In 2007 alone, the Ogden Museum mounted a memorial exhibition; solo shows opened at the Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL, and the Trois Gallery, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA. Later that year, Atlanta’s Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia showed Benny Andrews: A Georgia Artist Comes Home and Andrews’ series dedicated to civil rights activist John Lewis was exhibited at the Tubman Museum in Macon, GA. In 2014, this series was also the focus of a solo exhibition at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA.

In 2013, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presented Benny Andrews: There Must Be A Heaven, the first comprehensive retrospective since the artist’s death. In 2017, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery presented Benny Andrews: The Bicentennial Series, including paintings and drawings completed between 1970 and 1975. The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated color catalogue with an essay by Pellom McDaniels III, Ph.D., Curator of African American collections in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Library at Emory University in Atlanta. Benny Andrews: Portraits, A Real Person Before The Eyes was Michael Rosenfeld Gallery’s third solo exhibition of Andrews’ work in the fall of 2020, focusing on the vital role of portraiture throughout his career.

In 2022 The McNay Art Museum presented True Believers: Benny Andrews & Deborah Roberts, the first exhibition to examine the formal and thematic overlaps in the work of the two artists. That same year, Andrews’ Revival Series was the subject of an exhibition at High Museum of Art in Atlanta, GA. In 2023, Crisscrosses: Benny Andrews and the Poetry of Langston Hughes opened at The Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, with a companion exhibition at Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library titled At the Crossroads with Benny Andrews, Flannery O’Connor, and Alice Walker. That same year, in Andrews’ hometown, The Madison-Morgan Cultural Center in Madison, GA opened the permanent exhibit, The Andrews Family Legacy, exploring the important cultural contributions of Andrews and several of his family members. To mark the occasion, the seventeen paintings that comprise Andrews’ John Lewis Series were loaned to The Madison-Morgan Cultural Center by the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, GA, for a year-long exhibition. In 2024, The Ruth Foundation for the Arts in Milwaukee, WI presented the first major showing of Andrews’ art and archives in the retrospective exhibition Benny Andrews: Trouble, created in close dialogue with the Andrews-Humphrey Family Foundation and Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. With paintings, collages, and works on paper spanning four decades, bolstered by an innovative presentation of his archive, Benny Andrews: Trouble reflects the fullness of the artist’s practice, teachings, and advocacy work, which together constitute his greatest legacy: a call to action, a call to pay attention, and a call to always ask for more.

Andrews’ work has been included in numerous important group exhibitions, including the acclaimed traveling exhibitions Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties at the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY, which traveled to the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH and the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX (2014); Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power at its last two venues, the de Young Museum in San Francisco, CA and The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, TX (2020); The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse (2021–2023) organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia (Richmond); and Afro-Atlantic Histories, curated by Kanitra Fletcher of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (2022-2023). Internationally, Andrews’ work has been part of group exhibitions such as The Color Line: African American Artists and Segregation at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France (2016); Cultural Freedom and the Cold War at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Germany (2017); Tell Me Your Story: 100 Years of Storytelling in African American Art, Kunsthal KAde, Amersfoort, The Netherlands (2020); and The Modern City: Urban Experience and Identity in the Art of the United States, 1893-1976, organized by the Terra Foundation for American Art, at Pinacoteca de São Paulo, Brazil (2022). In 2024, Andrews’ work was featured in Edges of Ailey, curated by Adrienne Edwards at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY, and Surrealism and Us: Caribbean and African Diasporic Artists since 1940, at Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Fort Worth, TX.

Works by Benny Andrews are in over one hundred public collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; The Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, ME; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; Clark Atlanta University, Atlanta, GA; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA; Georgia State Art Collection, Atlanta, GA; Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC; Hampton University Museum, Hampton University, Hampton, VA; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, HI; Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Madison-Morgan Cultural Center, Madison, GA; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN; Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, WI; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, MO; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC has represented the Benny Andrews Estate since 2009.

[1] John Lewis, “Foreword,” in Benny Andrews: There Must Be a Heaven (New York: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, 2013), 7

Gallery Exhibitions

Press

Publications