Beauford Delaney

1901–1979

Beauford Delaney in his rue Vercingétorix studio, Paris, France, 1962; Photographer unknown, Courtesy of the Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

[I]n the selective and delicate formation and constant care of something we call plastic and is the essence of painting, that which cannot be said any other way except through the miracle of color life on canvas or paper.

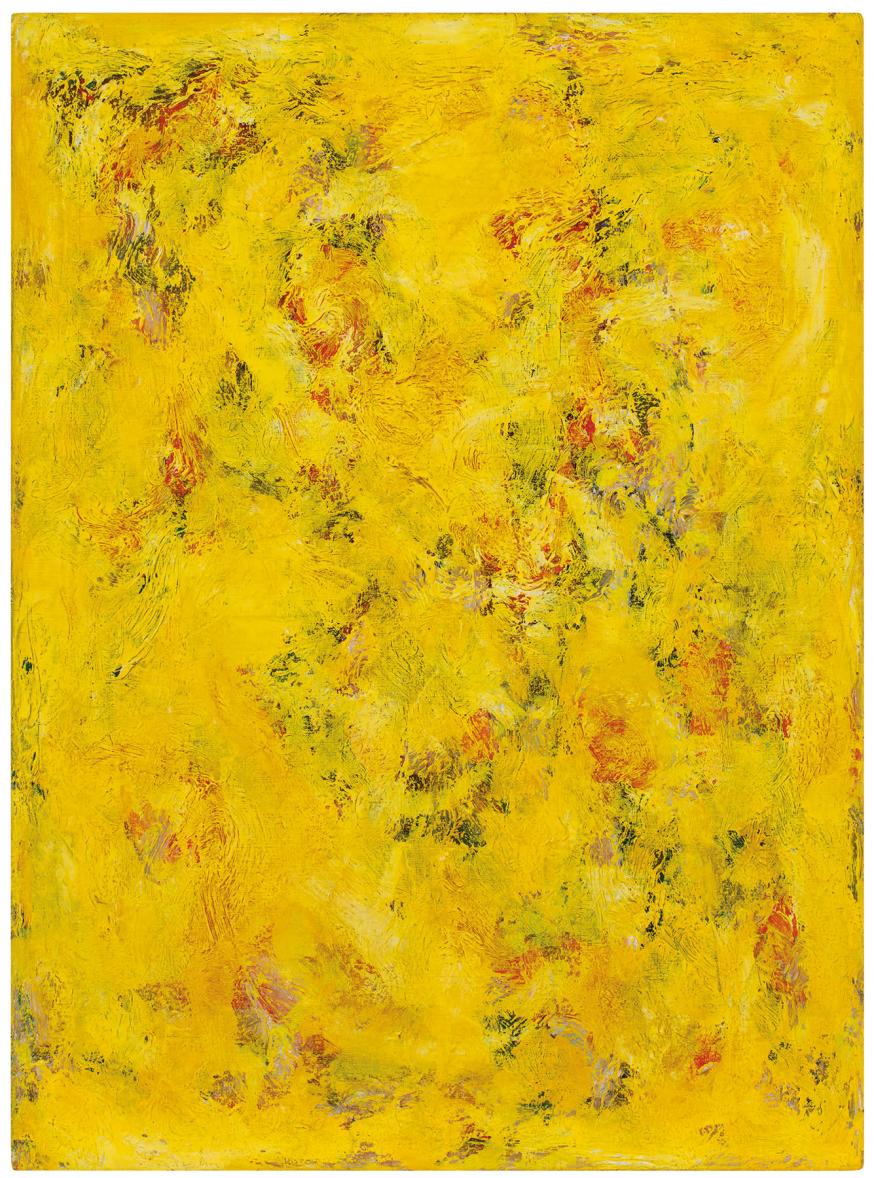

Beauford Delaney (1901–1979) was an extraordinary colorist whose style transformed from figurative expressionism to lyrical abstraction over the course of his storied career. Delaney was born and raised in Knoxville, Tennessee. He was the eighth of ten children his mother bore, but one of only a few who survived to adulthood. Beauford’s mother, Delia Johnson Delaney, had been born into slavery in 1865 and was a devout Christian who was dedicated to imparting her stringent religious beliefs to her children. However, her strictness did not prevent her from recognizing and nurturing her young son’s artistic talent. Beauford’s father, John Samuel Delaney (known as Sam), was a Methodist Episcopal preacher who spent much of his time traveling and ministering to black communities in need of churches. From 1910 to 1915, the family lived in Jefferson City, where church and religion dominated their social and intellectual activities. Despite the painful losses that afflicted the Delaney family, Beauford’s recollection of his childhood among his close, loving family was largely positive. In 1915, Sam was called back to Knoxville and the Delaney family returned to their original home.[1] Delaney attended Knoxville Colored High School, where prominent attorney and educator Charles W. Cansler was principal. Cansler brought Delaney’s artistic talent to the attention of notable Knoxville artist Lloyd Branson, who, with the assistance of artist Hugh Tyler, became an important instructor and mentor to the young artist. Delaney’s father died in April 1919. Later that year, rioting broke out in Knoxville after a Black American man, Maurice Franklin Mays, was accused of murdering a white woman. These events later became known as Knoxville’s “Red Summer.”

In 1923, Delaney left Knoxville for Boston, Massachusetts where he studied art at the Massachusetts Normal School (later the Massachusetts College of Art), the Copley Society, the Lowell Institute, and the South Boston School of Art. While in Boston, Delaney spent considerable time at local museums including the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, where he became familiar with impressionist painting, especially the work of Claude Monet and the portraiture of John Singer Sargent. In 1929, Delaney moved to New York City. Witnessing the economic blight brought about by the onset of the Great Depression, Delaney “felt an affinity with the multitude of marginalized races and classes in the city and instantly connected with these disenfranchised communities.”[2] He found work in the dance studio of Billy Pierce and “began rendering portraits of the studio's dancers and its socialite clientele (although he rarely received compensation for his artwork).”[3] In 1930, the Whitney Studio Galleries (later the Whitney Museum of American Art) included a selection of Delaney’s portraits in a group exhibition. Delaney received favorable reviews, and soon after, the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library mounted Delaney’s first solo show, Exhibit of Portrait Sketches by Beauford Delaney.[4] Around this time, Delaney began his studies at the Art Students League, where he worked with John Sloan and Thomas Hart Benton, among others.

Delaney soon found work with the mural division of the Federal Art Project (a New Deal program sponsored by the Works Progress Administration) and, in 1936, he worked with artist Charles Alston on murals at Harlem Hospital Center. During this time, Delaney was a member of the Harlem Artists Guild and frequented the salons and exhibitions held in Charles Alston’s studio, located at 306 West 141 Street. Known simply as “306,” the space served as a center for the most creative minds in Harlem, including among its regulars Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage, Romare Bearden, Richard Wright, Robert Blackburn, Countee Cullen, Ralph Ellison, and Gwendolyn Knight. Delaney was consumed by his own artistic vision and, while he enjoyed participating in the Harlem art scene, the artist remained closely connected to the bohemian Greenwich Village avant-garde community, forming lasting friendships with writers and artists such as Henry Miller, Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O’Keefe, and Al Hirschfeld. Throughout the 1940s and into the early 1950s, Delaney painted portraits, still lifes, street scenes, and modernist interiors, all executed with a dense impasto, undulating lines and bright colors reminiscent of the fauvist tradition. These vibrant paintings became known as Delaney’s Greene Street paintings; he lived and worked at 181 Greene Street in Greenwich Village from 1936 until 1952. Hovering between abstraction and figuration, the Greene Street works confound attempts to fit Delaney’s oeuvre into a definitive movement. Furthermore, although Delaney was accepted within New York’s elite circle of artists and intellectuals, he continued to experience marginalization because of his race, class, and sexuality. In 1950, Delaney received a two-month fellowship to Yaddo, a retreat for artists and writers in Saratoga Springs, New York. This experience was pivotal in Delaney’s personal and artistic growth; he wrote from Saratoga that he was “living and learning how to be a human and an artist.”[5] His time at Yaddo amplified his interest in experimenting with abstraction and intensified his aspiration to visit Europe.

In September 1953, Delaney followed in the footsteps of his dear friend James Baldwin and left New York City permanently for Paris, settling in Montparnasse. In 1954, his work was included in the ninth Salon des Réalités Nouvelles at the Palais des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris and, the following year, he had his first European solo show at Galería Clan in Madrid. Delaney moved to the Paris suburb of Clamart in December 1955 and supported himself through the occasional sale of his art as well as contributions from friends. Feeling a new sense of freedom from racial and sexual biases, he focused on creating non-objective abstractions. Delaney had met Baldwin in 1940, forming a close friendship that would last for the rest of Delaney’s life. In Clamart, Baldwin witnessed first-hand the transformation that Delaney’s art underwent in Europe: “a most striking metamorphosis into freedom.”[6] These works consist of elaborate, fluid swirls of paint applied in luminous hues, evoking pure, concentrated expressions of light. While his abstractions have clear ties to Monet’s studies of light, Delaney’s works are decidedly expressionist: the light Delaney sought to capture was not the actual light of day, but a transcendent, eternal, spiritual light. These works were first exhibited in a solo exhibition at the Galerie Paul Facchetti in 1960. In the months following the show, Delaney experienced economic distress and severe psychiatric difficulties in the form of paranoia and depression, which led to a suicide attempt in 1961. While he eventually recovered, the event resulted in a series of works he called his “Rorschach tests,” paintings where light is “enshrouded or overwhelmed, struggling to hold the forces of darkness at bay.”[7]

In 1962, he moved to a studio at 53 Rue Vercingétorix in the Montparnasse district of Paris, where he continued to produce his luminous abstractions alongside stirring, intimate portraits and scenes of Paris and the French countryside he often visited. Despite financial and psychological hardship, Delaney continued to work, exhibit, and live in Paris, enjoying success in both group and solo exhibitions throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. He was honored with an evening event and exhibition at the Centre Culturel Américain in Paris in 1969, and in 1973 Galerie Darthea Speyer mounted a major solo exhibition of his portraits and abstractions. In 1978, a year before his death, The Studio Museum in Harlem mounted Delaney’s first institutional retrospective comprising approximately seventy works and organized by cultural historian Richard A. Long.

Delaney died on March 26, 1979, in Saint-Anne Hospital in Paris following years of hospitalization for mental illness. A tutelle (trusteeship) was created by the French government in 1976 to handle Delaney’s affairs while he was institutionalized, assigning as guardians his close friends James Baldwin, Ahmed Bioud, Solange du Closel, Burton Reinfrank, Bernard Hassell, Darthea Speyer, and James LeGros. Obituaries charting the life of the famed portraitist appeared in international newspapers including The New York Times and International Herald Tribune.

In 2002, the High Museum of Art presented Beauford Delaney: The Color Yellow, curated by Richard J. Powell (and traveling to The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY; Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; and the Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA). In 2005, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts organized the exhibition Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris, which traveled to the Knoxville Museum of Art, Knoxville, TN; Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, SC; and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA. Catalogues with new scholarship also accompanied these important exhibitions. In 2017, the Knoxville Museum of Art mounted Gathering Light: Works by Beauford Delaney from the KMA Collection, and in 2020, the Knoxville Museum of Art presented Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door. Out of that latter exhibition grew Beauford Delaney’s Metamorphosis into Freedom which opened at the Asheville Museum of Art in Asheville, NC, in 2021 and traveled to the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, TN.

Delaney’s work is consistently included in critically acclaimed institutional group exhibitions that attest to his importance in the history of twentieth-century art. Major traveling exhibitions that have featured Delaney’s work include Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, which traveled throughout the United States from 2018 to 2020 after opening at the Tate Modern in London; United States of Abstraction: American Artists in France, 1946-1964 organized by the Musée d’Arts de Nantes, Nantes, France and Musée Fabre, Montpellier, France (2021); The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse (2021–2023) organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Virginia (Richmond); Afro-Atlantic Histories, curated by Kanitra Fletcher of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (2022-2023); When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration which opened at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, South Africa, and traveled to Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland (2022-2024); Southern/Modern curated by Jonathan Stuhlman of the Mint Museum in Charlotte, NC and Martha R. Severens (2023-2024); and Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France, 1946-1962 organized by Grey Art Gallery, New York University, New York, NY (2024-2025). In 2023, Delaney’s work was shown in God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin at Mead Art Museum, Amherst, MA; American Watercolors, 1880-1990: Into the Light at Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA; Higher Ground: A Century of the Visual Arts in East Tennessee at Knoxville Museum of Art, Knoxville, TN; and Black Artists in America: From Civil Rights to the Bicentennial, at Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, TN. In 2024, Delaney was featured in The Harlem Renaissance and TransAtlantic Modernism at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Century: 100 Years of Black Art at MAM at The Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ; and This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

In addition to museum exhibitions, Delaney’s life and work have inspired numerous books and scholarly essays. In 1998, David Leeming, Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Connecticut, published Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney (Oxford University Press), to be republished in 2024 with a new forward by Hilton Als. Articles about Beauford Delaney have appeared in the journals The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide,[8] Source: Notes in the History of Art,[9] Obsidian,[10] Black Renaissance/Renaissance Noire,[11] and Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art.[12] Essayist Rachel Cohen dedicated a chapter of her book A Chance Meeting: American Encounters to the encounter between Delaney and W.E.B. DuBois, which was published by Random House in 2004 and reissued in 2024 by New York Review of Books. In 2023, acclaimed poet Arlene Keizer released Fraternal Light: On Painting While Black – Poems for Beauford Delaney, published by The Kent State University Press, which won the Stan and Tom Wick Poetry Prize.

Delaney’s hometown of Knoxville, TN, continues to celebrate and promote the legacy of Beauford and his family. In 2016, the Knoxville Museum of Art acquired the largest institutional collection of Delaney’s art, selections of which are included in the museum’s permanent “Higher Ground” exhibition. In 2022, the University of Tennessee Libraries in Knoxville acquired the complete personal archive of Beauford Delaney, comprising correspondence, sketchbooks, loose sketches, and photographs of childhood, family, and friends, drawn from the artist’s estate. The collection, which will be available to scholars and researchers in the Betsey B. Creekmore Special Collections and University Archives at the UT Libraries, establishes Knoxville as a global destination for the study of Beauford Delaney and Black American art. The Delaney Museum, housed in the only remaining ancestral home of the Delaney family in Knoxville, will open in 2025.

Since 1995, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has championed the work of Beauford Delaney, working to bring him back from what Eloise Johnson has characterized as a “critical exile” in the decades following his death.[13] The gallery has mounted three solo exhibitions focused on the artist: Beauford Delaney: Paris Abstractions from the 1960s (1995); Beauford Delaney: Liquid Light – Paris Abstractions, 1954-1970 (1999), which was accompanied by a catalogue featuring an essay by Delaney biographer David Leeming; and, in the fall of 2021, Be Your Wonderful Self: The Portraits of Beauford Delaney, which was also accompanied by a catalogue publishing new scholarship by art historian Mary Campbell and a comprehensive, illustrated chronology. Be Your Wonderful Self traveled to the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans in 2022.

Now accepted as an essential contributor to American modernism, Delaney is represented in numerous prominent museum collections around the world including the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, ME; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France; Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris, France; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; Clark Atlanta University Art Museum, Clark Atlanta University, Atlanta, GA; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA; Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; Fisk University Galleries, Fisk University, Nashville, TN; Greenville County Museum of Art, Greenville, SC; Hampton University Museum, Hampton University, Hampton, VA; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; James E. Lewis Museum of Art, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD; Knoxville Museum of Art, Knoxville, TN; Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY; The Menil Collection, Houston, TX; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, MN; The Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC; The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, NY; Musée Cantonal des Beaux Arts, Lausanne, Switzerland; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; The Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; Philander Smith College, Little Rock, AR; Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY; Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY; Tennessee State Museum, Nashville, TN; Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, IL; University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA; University of Michigan Museum of Art, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC is Special Advisor and Representative of the Estate of Beauford Delaney.

[1] Much of the information about Delaney’s early life comes from David Leeming, Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney (London: Oxford University Press, 1998), 3-17.

[2] James Smalls, “Beauford Delaney,” in Joan Marter, ed., The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, Volume 1 (London: Oxford University Press, 2011), 49.

[3] Eloise Johnson, “Out of the Ashes: Cultural Identity and Marginalization in the Art of Beauford Delaney,”

Source: Notes in the History of Art vol. 24, no. 4 (Summer 2005), 46.

[4] Johnson, “Out of the Ashes,” 47-49.

[5] Delaney to Frank Scoville, September 10, 1950.

[6] James Baldwin, “On the Painter Beauford Delaney,” Transition no. 75/76 (1997), 89.

[7] Joyce Henri Robinson, in An Artistic Friendship: Beauford Delaney and Lawrence Calcagno, exhibition catalogue (University Park, PA: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennylvania State University, 2001), 13.

[8] Christopher Capozzola, “Beauford Delaney and the Art of Exile,” The Gay and Lesbian Review Worldwide vol. 10, no. 5 (September 2003).

[9] Eloise Johnson, “Out of the Ashes: Cultural Identity and Marginalization in the Art of Beauford Delaney,” Source: Notes in the History of Art vol. 24, no. 4 (Summer 2005).

[10] Joan Dempsey, “Waiting for You: Beauford Delaney as James Baldwin’s Inspiration for the Character Creole in ‘Sunny’s Blues,’” Obsidian vol. 12, no. 1 (Spring 2011).

[11] Patricia Hinds, “The Delaney Brothers – New York and Paris,” Black Renaissance/Renaissance Noire vol. 17, no. 2 (Fall 2017).

[12] Blake Oetting, “Looking for Beauford: The Green Street Paintings, 1936-1952,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art vol. 52 (May 2023).

[13] Johnson, “Out of the Ashes,” 52.

Gallery Exhibitions

Press

Publications