Alma Thomas

1891–1978

Alma Thomas in her studio, c.1968; Photographer Ida Jervis, Alma Thomas Papers 1894-1979, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

All artworks displayed above are currently available. To inquire about additional works available by this artist, please contact the gallery.

Biography

The use of color in my paintings is of paramount importance to me. Through color I have sought to concentrate beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.

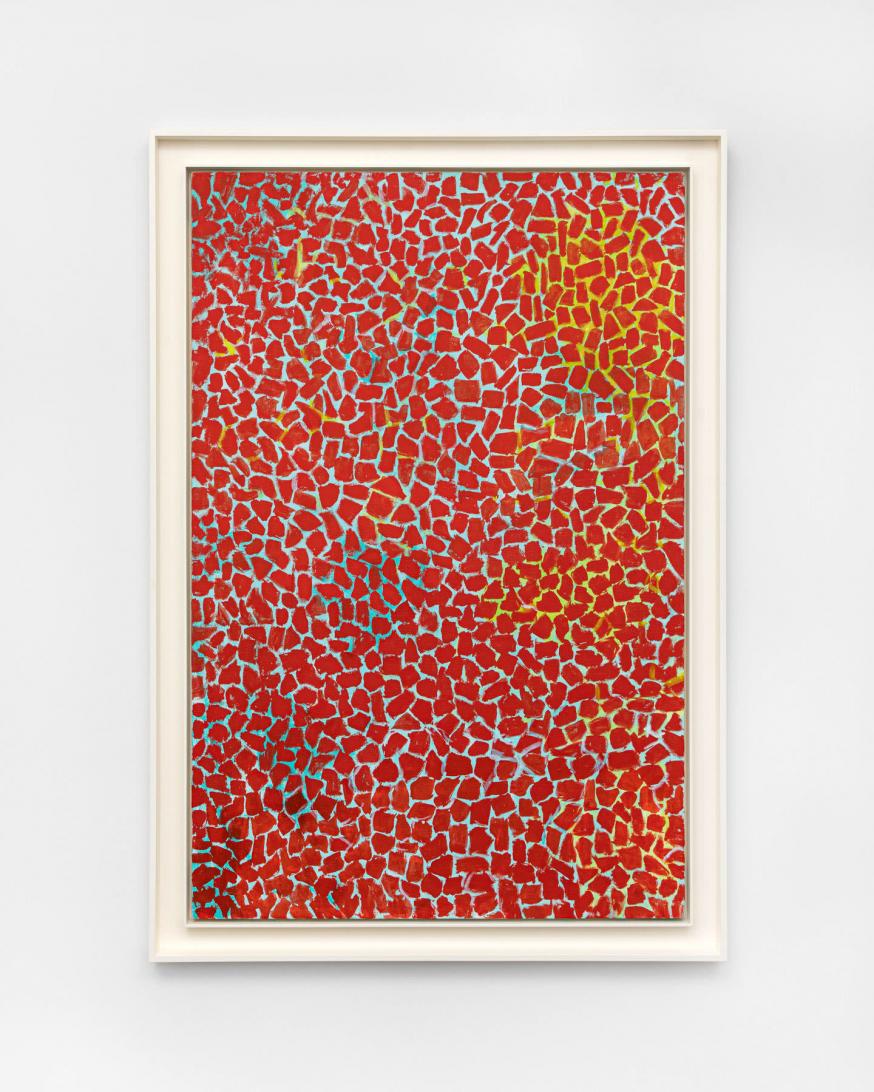

Known for her iconic abstract paintings comprised of rhythmic marks of exuberant color, Alma Thomas (1891-1978) was deeply interested in the optical effects of light and nature. Thomas was born in a suburb of Columbus, Georgia known as Rose Hill in 1891. She recalled that, as a child, “I would fall on the grass and look at the poplar trees and the lovely yellow leaves would whistle.”[1] Her parents, John Harris and Amelia Cantey Thomas, were both teachers, and Alma Thomas and her three younger sisters grew up around the educated adults their parents often entertained, including Booker T. Washington. In 1907, the family moved north to escape the rise of violence against Black Americans in Georgia and settled in Washington, DC. Thomas attended the Armstrong Manual Training High School and, from 1911 to 1913, the Miner Normal School for teacher training. She finished with a certificate to teach kindergarten and took a job in Delaware. In 1921, Thomas returned to DC and enrolled in courses at Howard University, studying home economics with the intent of becoming a costume designer. When James Herring founded the art department at Howard in 1922, Thomas became its first major; two years later, she was also the first to graduate with a BS in fine arts. From 1930 to 1934, Thomas took summer classes at Columbia University Teachers College, earning her master’s in art education. Throughout the 1930s, she continued to work in education and organize community art programs such as the Marionette Club, the School Arts League, and the Junior High School Arts Club. In 1943, Herring and Alonzo Aden founded the Barnett Aden Gallery, and Thomas became its vice president. Dedicated to avant-garde art, Barnett Aden was the first gallery in the nation’s segregated capital to exhibit work by both Black and white artists. In the late 1940s, Thomas became one of the Washington-area artists and art teachers affiliated with the “Little Paris Studio,” a collective started by Loïs Mailou Jones and Céline Tabary that met weekly and organized annual exhibitions. The group became an important venue for African American artists at the time.[2]

In the 1950s, Thomas started to develop the method and style that has earned her a place among the most innovative American painters of the twentieth century. She embarked on a decade-long formal study of art at American University and worked with painter Jacob Kainen. Departing from realism, Thomas loosened up her brushwork and began to focus more intently on fields of color. By the late 1950s, she found her voice in abstraction, patterning geometric shapes in rich colors against solid backgrounds. In 1960, at the age of sixty-nine, Thomas retired from teaching to devote her time exclusively to art. She painted in her kitchen, next to a window overlooking her garden, working on one canvas at a time. That same year, she had her first solo exhibition, at the Dupont Theatre Art Gallery. In 1963, her work was shown in New York City for the first time, at the Artists for CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) exhibition, mounted by the prestigious Martha Jackson Gallery. In 1972, Thomas was given two major solo exhibitions—Alma Thomas at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. With Alma Thomas, she became the first African American woman given a one-person show at the Whitney. Also in 1972, the mayor of DC, Walter Washington, declared September 8 to be Alma Thomas Day, and in celebration, local TV and radio stations aired programs about her life and work. She continued to exhibit in group and solo shows throughout the remainder of the decade, and in 1977, her work was included in the Corcoran’s 35th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting.

The monumental canvases Thomas created in the 1960s and 1970s were informed by the local abstract movement in DC known as the Washington Color School, which included Morris Louis, Sam Gilliam, and Kenneth Noland. However, her interest in color experimentation aligned her more closely to Josef Albers, Johannes Itten, and Wassily Kandinsky. Inspired by nature, recent discoveries in the sciences, and her own observations of earthly and celestial phenomena, Thomas’s work was devoid of overt political content. Her dedication to abstraction reflected her belief that modern art at its best could transcend political and historical concerns. “Thomas herself treated painting as only one facet of a larger, ongoing experiment,” wrote Jonathan Frederick Walz, curator of American Art at The Columbus Museum, Georga, “a relentless search for beauty that deepened her engagement with the art world as well as the greater, more palpable world of everything else.”[3] Her preference for abstract, joyously expressionistic, gestural strokes of vibrant color was not accompanied by a retreat from historical and social realities. The level of Thomas’ success in the 1960s and 1970s meant that she could devote herself exclusively to painting, but she continued to be a passionate advocate of arts education for underserved communities. In addition to her involvement with Artists for CORE, Thomas organized art programs and taught art classes to local youth. In 1975, Howard University honored her with its Alumni of Achievement Award, a recognition of her importance to both the history of art and the local African American communities touched by her considerable talent and dedication as an artist and a teacher.

In 1998, the Fort Wayne Museum of Art mounted the artist’s first traveling retrospective: Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings, which traveled to Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, FL; New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ; Anacostia Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; and The Columbus Museum, Columbus, GA. Eighteen years later, in 2016, The Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and The Studio Museum in Harlem revisited Thomas’ life work, co-organizing a major survey exhibition and an award-winning monograph that featured new scholarship on her important work and influential legacy. In July 2021, Chrysler Museum of Art and The Columbus Museum co-organized the solo exhibition Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful, which traveled to The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC and The Frist Art Museum, Nashville, TN, before closing at The Columbus Museum in summer 2022. The next year, in 2023, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which has the largest collection of works by Alma Thomas in the world, opened the traveling exhibition Composing Color: Paintings by Alma Thomas.

Thomas’ work has regularly been featured in important historical group exhibitions, including Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) and Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil (2018); Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (2018); Peindre la nuit, Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, France (2018); Generations: A History of Black Abstract Art at The Baltimore Museum of Art (2019); Afrocosmologies: American Reflections at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT (2019); The Fullness of Color: 1960s Painting at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (2019); Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power organized by the Brooklyn Museum (2018-19); Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem (2021); African American Art in the 20th Century: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond, organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (2019-21); Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (2021); Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art (2021), organized by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and In the Balance: Painting and Sculpture, 1965–1985 (2022), at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY.

Michael Rosenfeld Gallery has exhibited the work of Alma Thomas consistently for the past thirty years, including in the solo exhibitions, Alma Thomas: Phantasmagoria, Major Paintings from the 1970s (2001) and Alma Thomas: Moving Heaven and Earth - Paintings and Works on Paper, 1958-1978 (2015), and the group exhibition Stroke! Beauford Delaney, Norman Lewis and Alma Thomas (2005).

In 2014, President Barack Obama oversaw the acquisition of work by Alma Thomas for the White House Collection. Works by Thomas may be found in the permanent collections of several prominent American institutions, including of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; the Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA; Colby College Museum of Art, Colby College, Waterville, ME; The Columbus Museum, Columbus, GA; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, NC; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA; Smith College Museum of Art, Smith College, Northampton, MA; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY; Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; The White House Historical Association, Washington, DC; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY.

[1] Alma Thomas, autobiography, undated, Alma Thomas Papers, box 1, folder 2, page 2.

[2] Tritobia Benjamin, The Life and Art of Lois Mailou Jones (New York: Pomegranate Press, 1994), 49 as cited in Catherine Bernard, “Patterns of Change: The Work of Lois Mailou Jones,” 2002, Anyone Can Fly Foundation website. http://www.anyonecanflyfoundation.org/library/Bernard_on_Mailou_Jones_essay.html#22, accessed October 2012.

[3] Jonathan Frederick Walz and Seth Feman, “Then the Light Would Come Around,” Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021).

Gallery Exhibitions

Press

Publications